For many years it was widely believed that the indigenous population of Australia lived only a hunter-gatherer lifestyle before European settlement. However, there is growing evidence that Australia’s first nations people practised unique forms of agriculture that shaped Australia’s landscape [1].

Indigenous agricultural practices were significantly different from the traditional farming of crops and domestication of animals practised by the rest of the world. On the northern islands of the Torres Strait, there were some agriculture and foraging techniques learned from New Guinea (including raising pigs and cultivating crops). However, these methods of agriculture were not used by the inhabitants of southern Torres Strait, and never reached the Australian mainland [1]. Australia’s unique environment, isolation and the integral role the land has in Aboriginal culture resulted in the creation of unique agricultural practices. This insight touches on a few of these practices.

Source: AgriEducate

Fire-stick farming

Fire was an integral part of traditional aboriginal land management, used for hunting and shaping the landscape. Indigenous people had a keen understanding of the land, its flora, fauna and seasons, and this allowed them to effectively use fire as a sustainable land management technique.

Fire used in small mosaic patterns, carefully planned and managed had the ability to:

- Encourage the regeneration and growth of native grasses and plants, which in turn produces new feed for animals (kangaroos in particular)

- Prevent bushfires by reducing scrub and fuel

- Promote biodiversity

After European settlement, these practices diminished. Resulting in the growth of unmanaged thick scrub prone to intense bushfires [2].

Budj Bim eel traps

Situated in south-west Victoria, the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape provides irrefutable evidence of Indigenous agricultural activities in Australia. Volcanic rocks, formed by the now dormant volcano of Budj Bim, were used by the local Gunditjmara people to engineer aquaculture structures. These structures included weirs and ponds to manage water flows from Lake Condah and fish traps that were used to trap eels [3].

Photo: Damien Bell

Budj Bim could possibly be one of the world’s oldest carbon-dated at 6,600 years old) and largest aquaculture sites. This year the site was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List [4] after a decade of lobbying. Budj Bim is the first World Heritage site in Australia that was nominated and listed exclusively for its Aboriginal cultural values.

The extensive size and complexity of the Budj Bim cultural site also challenge the concept that all Indigenous people were nomadic [4]. The cultural site holds the remains of wooden, thatched dome and even stone dwellings. It is hoped that studying this complex aquaculture site will help Indigenous communities to create new industries including eel aquaculture and wild rice agriculture [5].

Image sourced from Engineers Australia

Image sourced from Engineers Australia

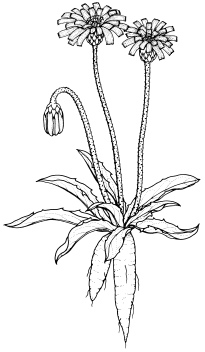

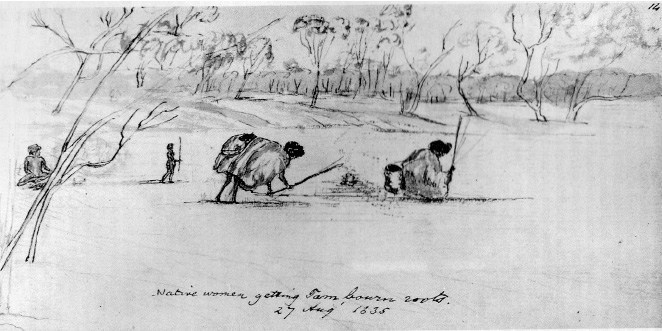

Yams fields

It is estimated that there are 6,000 edible native plants in Australia [6]. One of the most notable food sources were Yams, a high-starch tuber found in many regions of Australia in different varieties. Aboriginal women in these areas would grow and harvest Yams, found in crop-like pastures, but in such a way that allowed the tubers to regrow in the next season [1].

Unfortunately, the introduction of grazing animals and rabbits have significantly reduced the native growth of yams. Over the past decade, there have been efforts made to revitalise the cultivation of Yams and similar native foods. Of these native foods, the Murnong (Yam Daisy) is being recognised as a nutritious superfood and is making its way into menus and restaurants [7].

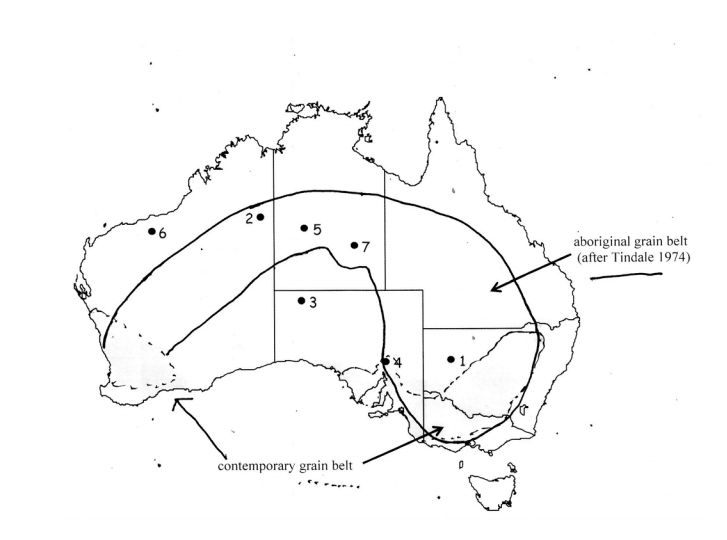

Native Grains

Accounts from early European explorers describe pastures and fields of native grains and grasses maintained by the aboriginal peoples. There is also evidence that Aboriginal people were among the worlds first bakers. Grindstones, used to grind seeds and grain to create flours, have been found and dated at up to 30,000 years old. It is estimated that aboriginal grain fields were grown in dry climates across a large portion of Australia, far exceeding our modern-day grain-belt regions [8].

There is still much to learn about Australia’s indigenous agricultural history. Unfortunately, a lot of this history has been lost and is still greatly unappreciated. Learning more about Indigenous agricultural practices could possibly refine modern land management techniques, establish new agricultural industries and help us create a more sustainable future.

Take the time to explore and

learn more about the culture and practices of Aboriginal people in your

area. If your company is working in areas

whereas Native Title Claims has been registered or just needs some assistance

in contacting a group please contact us via enquires@integratesustainability.com.au

or phone 9468 0338.

References

| [1] | M. Monroe, “Australia: The Land Where Time Began,” 19 February 2012. [Online]. Available: https://austhrutime.com/agriculture.htm. [Accessed 26 July 2019]. |

| [2] | C. Gillies, “Traditional Aboriginal burning in modern day land management,” March 2017. [Online]. Available: https://landcareaustralia.org.au/project/traditional-aboriginal-burning-modern-day-land-management/. [Accessed 29 July 2019]. |

| [3] | Visit Victoria, “Regional Spotlight: Budj Bim Cultural Landscape,” 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.visitmelbourne.com/things-to-do/aboriginal-victoria/regional-spotlight-budj-bim-cultural-landscape. [Accessed 25 July 2019]. |

| [4] | J. Korff, “Aboriginal land management & care,” 17 July 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.creativespirits.info/aboriginalculture/land/aboriginal-land-care. [Accessed 25 July 2019]. |

| [5] | C. Wilson, “Rethinking Indigenous Australia’s agricultural past,” 15 May 2014. [Online]. Available: https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/archived/bushtelegraph/rethinking-indigenous-australias-agricultural-past/5452454. [Accessed 26 July 2019]. |

| [6] | B. Evans, “Indigenous Agriculture: Australia’s hidden past,” 21 March 2016. [Online]. Available: https://theplanthunter.com.au/culture/dark-emu-book-review/. [Accessed 29 July 2019]. |

| [7] | S. Verass, “This native superfood is 8 times as nutritious as potato and tastes as sweet as coconut,” 27 February 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.sbs.com.au/food/article/2018/02/27/native-superfood-8-times-nutritious-potato-and-tastes-sweet-coconut. [Accessed 29 July 2019]. |

| [8] | AgriEducate, “THE FIRST FARMERS,” 29 May 2017. [Online]. Available: https://agrieducate.com.au/2017/05/29/the-first-farmers/. [Accessed 29 July 2019]. |