Download PDF: ISPL Insight – WA unique biodiversity

Biological diversity – or biodiversity – is the term given to the variety of life on Earth. Australia has a high percentage of endemic species (meaning, they occur nowhere else in the world). More than 80% of Australia’s flowering plants and land mammals are endemic, as are 88% of our reptiles, 45% of our birds and 92% of our frogs. Western Australia is home to many of these plants and animals and has some of the richest and most unusual biodiversity on Earth, much of which occurs nowhere else and is recognised as being significant at both national and global scales.

The wetlands in WA support a rich natural heritage of plant and animal life. These systems include tidal mangroves, sand and mudflats, coastal lakes, subterranean aquatic systems, swamps and marshes. The coastal marine biodiversity of WA is ranked second highest out of 18 of the world’s marine biodiversity hotspots (based on species richness and endemism) and fourth lowest in terms of threatening processes.

The wetlands in WA support a rich natural heritage of plant and animal life. These systems include tidal mangroves, sand and mudflats, coastal lakes, subterranean aquatic systems, swamps and marshes. The coastal marine biodiversity of WA is ranked second highest out of 18 of the world’s marine biodiversity hotspots (based on species richness and endemism) and fourth lowest in terms of threatening processes.

Western Australia is home to:

- 141 of Australia’s 207 mammal species, 25 unique to the state;

- more than 400 reptile species, more than 40% unique to the state;

- more than 1,600 fish species;

- hundreds of thousands of invertebrate species; and

- one of the most diverse and unique floras in the world, with over 210 vascular plant families, and 50-80% of species being unique to the state in the largest of these families.

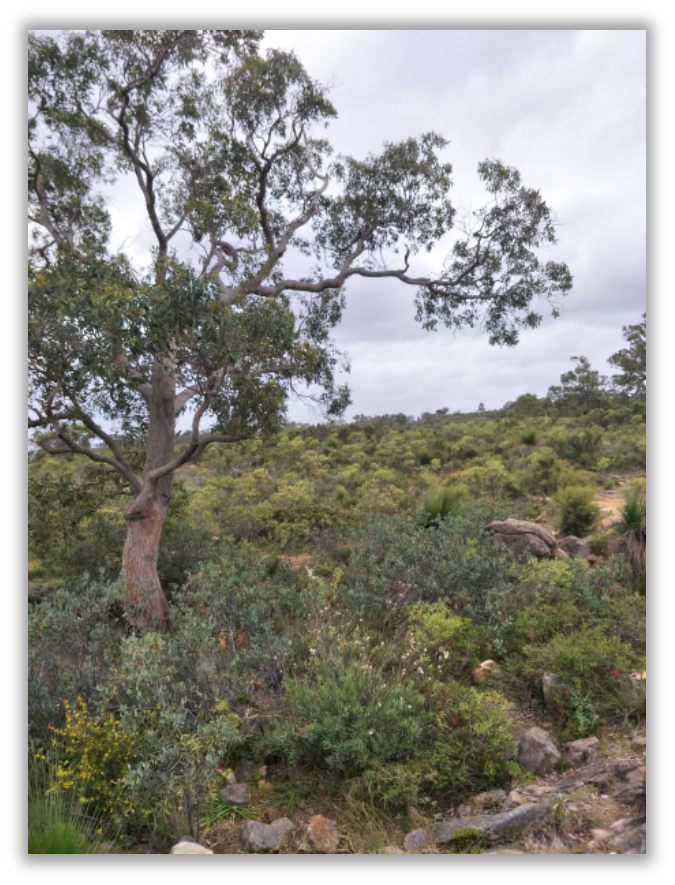

The state’s south-west, in particular, has some of the richest diversity of plants and animals on earth. Southwest Australia is recognised as one of the world’s 35 recognised biodiversity hotspots. This means our south west is a region “where exceptional concentrations of endemic species are undergoing exceptional loss of habitat”. The region is about the size of England, which has about 1,500 species of vascular plants (all plants except ferns and mosses), 47 of them found nowhere else. Contrast that with Southwest Australia, which harbours an astonishing 7,239 vascular plant species, almost 80% of which are found nowhere else in the world (Alphen, 2016).

Source: Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (Department of Parks and Wildlife Service)

Impacts to Biodiversity

The south-west of the State has experienced significant impacts to biodiversity values from broad-scale land clearing for agriculture (especially in the 1920s to 1980s), expansion of urban areas, and development of infrastructure and use of natural resources. This has led to loss and fragmentation of habitats, with a range of biological effects, which include the slow dismantling of ecological communities and species habitat – resulting in eventual species extinctions and loss of biodiversity richness

Land and natural resource use practices have also left a legacy of problems that have set in train a number of degrading processes which continue to impact on biodiversity. These include:

Land and natural resource use practices have also left a legacy of problems that have set in train a number of degrading processes which continue to impact on biodiversity. These include:

- salinization and waterlogging of ecosystems;

- Phytophthora dieback in the south western parts of the State;

- over-grazing of native vegetation by domestic animals, loss of soils and altered hydrology in the pastoral rangelands;

- over-exploitation of native plants and animals; and

- altered fire regimes

A primary cause of biodiversity loss is a general lack of public awareness and appreciation of biodiversity and its values, this disconnect with nature often results in a lack of empathy with our natural heritage, and biodiversity. The growing demands of an expanding human population (often associated with changes in demography) and growing global markets are placing additional pressures on our natural wealth with long-lasting consequences. Coupled with persistent biophysical threats and socioeconomic causes is human-induced climate change, which is projected to exacerbate biodiversity loss through increased risk of species extinctions and ecosystem decline, especially among those already at risk and limited in their climatic range (Conservation, 2006).

Protecting our Unique Biodiversity

The beginning of biodiversity conservation in WA is rooted in the setting aside of land by the State for the protection of flora and fauna in the late 1800s and early 1900s when the first reserve declared was in September 1899 for the purpose of the ‘Protection of Boronia’ near Albany; and the first national park, Greenmount National Park (which has now become John Forest National Park) was established in 1900 on the outskirts of Perth.

In 2016 the Western Australian government passed the Biodiversity Conservation Act, which will eventually fully replace both the Wildlife Act 1950 and the Sandalwood Act 1929. On 2 December 2016, several parts of the new Act were proclaimed and came into effect on 3 December 2016. They include:

- the ability for the Minister to approve “Biodiversity management programmes;”

- the ability for the Minister to agree to “Biodiversity conservation agreements”;

- the ability for the Director General of Parks and Wildlife to enter into “Biodiversity Conservation Covenants” with private landholders; and

- the ability for the Minister to make regulations for certain matters identified in the Act.

While the Act provides new arrangements for Biodiversity Conservation Covenants, these arrangements do not replace or invalidate existing registered Nature Conservation Covenants which will continue unaffected by the Biodiversity Conservation Act.

While the Act provides new arrangements for Biodiversity Conservation Covenants, these arrangements do not replace or invalidate existing registered Nature Conservation Covenants which will continue unaffected by the Biodiversity Conservation Act.

Provisions that replace those existing under the Wildlife Act and Sandalwood Act (including threatened species listings and controls over the taking and keeping of native species) and their associated Regulations cannot be brought into effect until the necessary Biodiversity Conservation Regulations have been made. Work on the drafting of the new Biodiversity Conservation Regulations is underway (Service, 2017).

If you or your organisation have any questions regarding biodiversity protection or require any assistance in biodiversity restoration please contact Integrate Sustainability on 08 9468 0338 or enquiries@integratesustainability.com.au.

References

Alphen, S. V. (2016, February 18). Australias South West: A Hotspot for Wildlife nd Plants that Deserve World Heritage Status. Retrieved from The Conversation: https://theconversation.com/australias-south-west-a-hotspot-for-wildlife-and-plants-that-deserves-world-heritage-status-54885

Conservation, D. o. (2006). Draft – A 100-year Biodiversity Conservation Strategy for Western Australia: Blueprint to the Bicentenary in 2029. Government of Western Australia.

Higgs, P. (2016, July 26). The State of Dieback. Retrieved from Gaia Resources: https://www.gaiaresources.com.au/state-dieback/

Service, D. o. (2017, July 27). Biodiversity Concervation Act 2016. Retrieved from Department of Parks and Wildlife Service: https://www.dpaw.wa.gov.au/plants-and-animals/468-biodiversity-conservation-act-2016