As companies move towards a more sustainable business model, becoming cleaner, greener, and more transparent with their operations, it is important to also consider the current socio-political climate we exist in. We need to ensure our activities are morally, ethical, and socially acceptable, as well as being environmentally and economically sound.

To this end, companies are now also being assessed and rated against each other for their social impacts and considerations, as well as their environmental sustainability and economic success; and these ratings are being publicly reported and used to rank businesses from an ethical standpoint. Investors and governments, as well as everyday consumers, are using this information when selecting products and services, assessing assets or investments, and considering regulatory approvals.

Given these changes, it is prudent for a company to look inwards and consider whether its own business dealings and actions are ethical and whether they would meet a moral standard, as well as achieving traditional business goals and outcomes, even when not being publicly rated and reported.

One aspect of the mining industry in particular, which compels this self-reflection is how we engage with the Traditional Owners of the land we work on. Are we conducting these dealings with integrity, honour and respect; even when what we are doing is deemed legal – and exactly what are ethical business practices when it comes to dealing with another group’s culture, expectations, history and birthright?

Firstly, let us establish, what are ‘Ethics’ and ‘Morals’?

The Oxford English Dictionary defines ethics as: “moral principles that govern a person’s behaviour or the conducting of an activity.”

Which is tightly linked with the idea of ‘morals’, which are defined as: “of or pertaining to the distinction between right and wrong, or good and evil, in relation to the actions, volitions, or character of responsible beings; ethical”.

Essentially, morals and ethics are associated with the characterisation of actions as right or wrong; however, how we see the world (and therefore what is considered right or wrong in our eyes) is governed by our own experiences, norms, values, culture and learning.

According to Jones and Parker et al (2005), ethics regulates areas and details of behaviour that lie beyond governmental control. It is important to note that “law” and “ethics” are not the same; nor are the “legal” and “ethical” courses of action in each situation necessarily the same. Statutes and regulations set forth the “law”, and although an action or activity is ‘legal’, does not necessarily imply it is ‘ethical’ (e.g. slavery, apartheid etc. were all once legal, but could hardly be called ethical practices).

Essentially, ethics tries to create a sense of right and wrong, and are broader than what is considered legally acceptable (or even socially acceptable according to public opinion). However ethical behaviour and practices vary from culture to culture, and the definition of them can be challenging.

Why are they important in business?

Ethics are important as they guide the conduct, decision making and practices of an entity or person. Michael Josephson, founder and president of the non-profit Joseph & Edna Josephson Institute of Ethics explains “in business, how people judge your character is critical to sustainable success because it is the basis of trust and credibility. Both of these essential assets can be destroyed by actions which are, or are perceived to be unethical” (Josephson, 2015).

Recent events in the mining industry which bring this relationship between ethical practices and legal activities to the fore include impacts to, or removal of places or other aspects of Aboriginal Heritage under legally sanctioned and approved processes, such as section 18 of the Western Australian Aboriginal Heritage Act (1972). Although due legal process is being followed and permission is legally granted to disturb places of significance, the perception, and ethics of doing so may remain a question for consideration.

Application of Ethics to Engagement with Indigenous Australians in the Mining and Resources industry

While activities undertaken by the resources industry are regulated in terms of the requirements for addressing and dealing with aspects of Aboriginal Heritage (such as survey requirements, notification and documentation – although there are arguments for reform in this space too); there is relatively little guidance on the application of that law beyond legal obligations. How a company actually engages with the stakeholders is somewhat discretionary unless it is a formal requirement of an authorisation process.

Additionally, much of the Government’s guidance for engaging with Traditional Owners simply speaks to “consultation processes” rather than clarifying how these should be conducted. How then are we to act ‘ethically’ from an objective business standpoint during the consultation and engagement processes, such that what we consider to be ethical, fair and equitable is also considered to be such to another group (in this case the Traditional Owners) we work and engage with?

Is simply ‘following the law’ acceptable and ethical, or do we need to go beyond that in our engagement with stakeholders?

In the recent example of the blasting of the Juukan Gorge cave by Rio Tinto in May 2020, all the appropriate legal obligations had been met and the relevant approvals process followed. However, upon further archaeological investigation, additional information was brought to light the age of the caves and the presence of artefacts.

Despite this, the current legislation did not allow for renegotiation of the ministerial consent [the approval to disturb the site] on the basis of new information (Wahlquist, 2020).

It is at these times that ethical considerations bridge the gap between what is ‘legal’ and what is ‘right’. Although it was legal to disturb the site, in light of the new information, was it ethical, and who is to be the judge of that? Food for thought! So, what actions can we take to ensure we are acting ethically when we engage with our stakeholders, and particularly with the Traditional Owners of the land we live and work on?

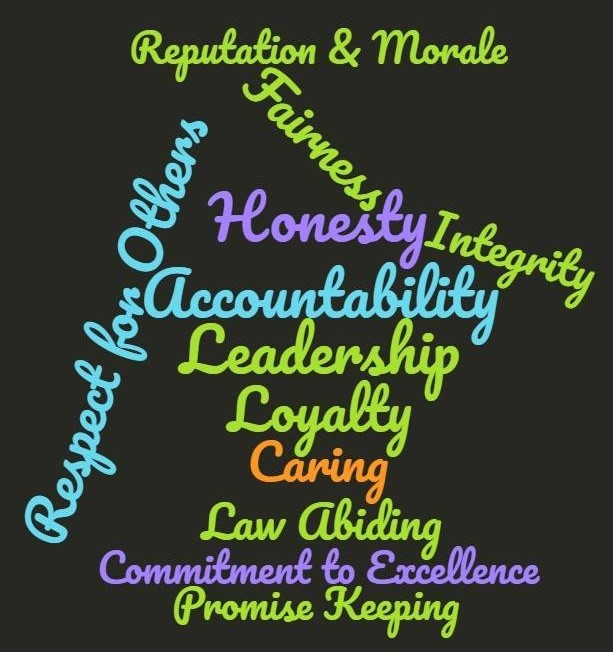

Josephson’s 12 key principles of ethical behaviour

Integrate Sustainability regularly engages with Indigenous Australians in all aspects and phases of mining activities, from exploration, through to construction and operation, rehabilitation and closure; and aims to conduct its activities according to the 12 ethical principles defined by Josephson (2015).

1. Be honest in all communications and actions

When engaging with Traditional Owners, be trustworthy and honest. This means not deliberately misleading or deceiving through misrepresentation, overstatement, partial truths, or selective omission. Be candid and forthright, and this will build a trusting relationship between all parties.

2. Maintain personal integrity

Trust is also earned through personal integrity (showing consistency between one’s thoughts, words, and actions). Integrity also means doing the ‘right thing’ in the face of personal (or business) cost, even when there may be pressure to do otherwise or competing obligations and interests. We are honourable, upright, and scrupulous in our dealings with all stakeholders.

3. Keep promises and fulfil commitments

We do not create justifications for escaping our commitments, or unreasonably or unjustly interpret agreements to rationalise non-compliance. Every reasonable effort to fulfil our obligations in both the letter and the spirit of the law is made. This also leads back to trustworthiness.

4. Be loyal within the framework of other ethical principles

While we remain loyal to our organisation, our clients and their interests when engaging with or negotiating with the Traditional Owners, we do not put loyalty above other ethical principles. Neither do we use loyalty to others as an excuse for unprincipled conduct. We avoid conflicts of interest and do not use the information for personal or company gain. This justifies trust in our company.

5. Strive to be fair and just in all dealings

We remain fundamentally committed to fairness, manifesting a commitment to justice, not exercising power arbitrarily, nor taking undue advantage of another’s mistakes or difficulties. We are committed to the equal treatment of individuals, tolerance for and acceptance of diversity. This means remaining open-minded; being willing to admit when we are wrong and, where appropriate, changing our positions and beliefs.

6. Demonstrate compassion and a genuine concern for the well-being of others

We always consider the consequences of our actions (and by extension, those of our clients) on the Traditional Owners of the land we are working, as they are the ones who are affected by our decisions and actions. We seek to conduct our activities in a manner that causes the least harm and the greatest positive good, for future generations as well as the present.

7. Treat everyone with respect

We are courteous and treat all people with equal respect and dignity regardless of sex, race or national origin, and demonstrate respect for the human dignity, autonomy, privacy, rights, and interests of all those who have a stake in our decisions.

8. Obey the law

We abide by laws, rules and regulations relating to our business activities.

9. Pursue excellence all the time in all things

We constantly strive to increase our proficiency in all areas of our responsibility and aim to remain well informed with all aspects of our dealings with the Traditional Owners we work with, taking our previous experience and learning from it.

10. Exemplify honour and ethics

Integrate Sustainability seeks to create an environment in which ethical decision making and principled reasoning are a priority when engaging with the Traditional owners of the land on which we work. We remain conscious of the responsibility we hold and seek to be ethical role models by our own conducts.

11. Build and protect the company’s good reputation and the morale of its employees

Our reputation is important to us and we actively avoid undermining the respect of the Traditional Owners we engage with.

12. Be accountable

We accept and acknowledge our personal and the company’s responsibility for our decisions and ensure they remain ethical, just, fair, and equitable in all our consultation processes and engagement.

While Josephson’s principles stated above are applied to how we engage with Indigenous stakeholders, they can be universally applied to all business and personal relationships and hold true regardless of culture or social setting. Early adoption of ethical practices and business conduct will provide a firm foundation for the development of effective stakeholder engagement.

If you are in need of advice or support with engaging with the stakeholders associated with your projects and would like to discuss how we might be able to help, please contact Integrate Sustainability on 08 9468 0338 or enquiries@integratesustainability.com.au.

References

DMIRS. (2004, July). Consultation Guidelines with Indigenous People by Mineral Explorers. Retrieved from https://www.dmp.wa.gov.au/Documents/Minerals/Minerals-Consultation_Guidelines_with_Indigenous_People.pdf

Jones C., P. M. (2005). For Business Ethics.

Josephson, M. (2015, January 13). 12 Ethical Principles for Business Executives. Retrieved from ISBO Global Leadership Bulletin: http://www.standardizations.org/bulletin/?p=133

Wahlquist, C. (2020, May 26). Rio Tinto blasts 46,000-year-old Aboriginal site to expand iron ore mine. Retrieved from The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/may/26/rio-tinto-blasts-46000-year-old-aboriginal-site-to-expand-iron-ore-mine

Featured Image: Designed by Freepik