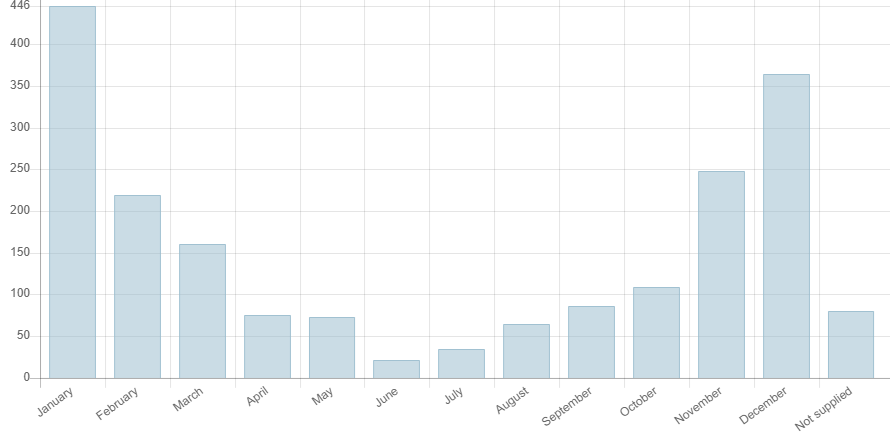

Austracantha minax is commonly known as the Jewel spider or the Christmas spider. Other common names for the species include “six-spined spiders” and “spiny spiders” in reference to the spine-like projections on their abdomens, that makes them easy to identify (Atkinson 2011). The Christmas Spider can be found at this time of the year, between November and January. Their small bright yellow, white and black bodies decorate the environment throughout summer, as we can see in Figure 1 (The Atlas of Living Australia 2019).

You may ask, “Where do Christmas spiders go for the rest of the year?” They don’t go anywhere; they are just harder to spot. This happens because the juveniles are out from autumn to spring and they are much harder to see during the earlier stages of their life cycle. As juveniles, the Christmas Spider and their webs are very small, and their colours are less distinct than those of the adult females that we usually see. From the middle of spring, the spiders undergo their final moulting stages towards becoming fully grown adults. They reach a body length around 12 mm for females, and 5 mm for males (Framenau 2014).

You don’t have to worry about this arachnoid, they are harmless. Although many specialists think their toxicity is uncertain, this spider is considered to be too small to cause human illness. They are not very aggressive (they rarely bite) and their venom glands are only normally used to subdue prey (Atkinson 2011). If you are bitten by this spider, you will probably feel temporary reactions like redness, swelling, or itching can sometimes be experienced on the bite area. Overall, these spiders when disturbed, will try to escape by clambering upside-down along their support threads to nearby shelter (Framenau 2014).

According to “The Atlas of Living Australia” there are five subspecies of Austracantha minax:

Austracantha minax astrigera – Found in mainland Australia. Characterised by an abdomen that is mainly black on top and patterned with yellow on the bottom surfaces. The spines are thicker and curved, with the rear spines visibly longer than the side spines. The sternum (chest) has a bright orange spot.

Austracantha minax minax – Found in mainland Australia and surrounding islands, including Tasmania. Characterised by yellow to orange colouration being prevalent on the bottom of the abdomen and on the legs. The spines are more slender and are barely arched. The rear spines are almost the same length as the side spines.

Austracantha minax hermitis – Endemic to the Montebello Islands. The abdomen is pearl grey on top. The legs, cephalothorax, and the sternum are bright orange.

Austracantha minax leonhardii – Found in central Australia. Characterised by reddish cephalothorax and mandibles. The legs are brownish-yellow, with only the second and third segments from the last (the tibiae and metatarsi) showing black rings at the tip.

Austracantha minax lugubris – Found in mainland Australia. Characterised by legs and abdomen that are mostly black with no bright markings. The spines are slender and taper downwards.

The Austracantha minax female has different physical characteristics to the male – this is known as sexual dimorphism. The female Christmas Spider can mate with multiple males during a single reproductive cycle. The successful male may try to defend the female shortly before and after mating. If given the chance the female will still readily mate with other males (Sinclair-Jones 2013) until the female enters a refractory period and ceases to be receptive to further matings. This usually happens within a few days of mating. During this time the female will aggressively attack and drive away all courting males. At the beginning of their life, the Christmas spiders develop within an egg sac, laid by females during autumn each year. Towards the end of autumn, the spiderlings emerge (Atkinson 2011).

Christmas spiders are opportunistic predators that use their legs to entangle small flying insects, like flies and mosquitoes, on their webs. Some scientists believe that they increase their foraging efficiency by attaching their webs to neighbouring webs (Waldock, J. M. and Scharff, N. 2014). Then, using the neighbour`s webs, they can extend their webs to other prey-rich areas (Figure 4). Another unusual behaviour of the Christmas spiders is that they make their support wires visible to larger animals. This is believed to prevent larger animals from inadvertently entering the nets and damaging them.

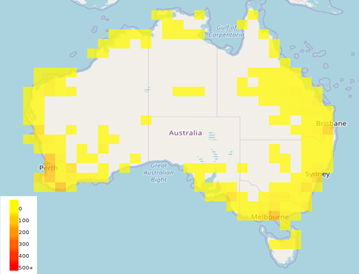

Christmas spiders are considered endemic to Australia. They can be found across the continent as well as on neighbouring islands including Tasmania, Barrow Island (Western Australia) and the Montebello Islands. They are most common in the southern mainland, southern Queensland and New South Wales, across Victoria and southern Australia, to Western Australia. Although they can be found in the Northern Territory, they are less common and their place is usually occupied by species of the genus Gasteracantha (The Atlas of Living Australia 2019).

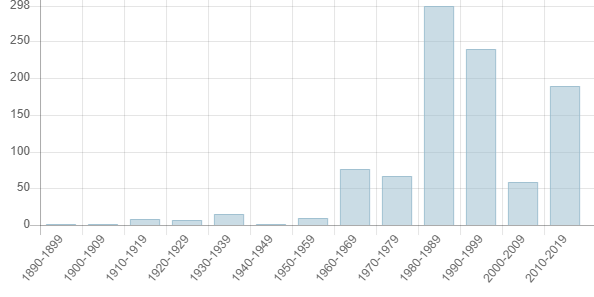

In Figure 5, you can see a map depicting the density of Christmas Spiders in Australia. In Perth WA, a large number of spiders can be found in gardens. Since 1890, Living Australia Atlas has been reporting the occurrences of Christmas Spiders in Western Australia. They have reported a total of 993 occurrences of the Austracantha minax, of which only two were identified as Austracantha minax lugubris (as shown in Figure 6) (The Atlas of Living Australia 2019).

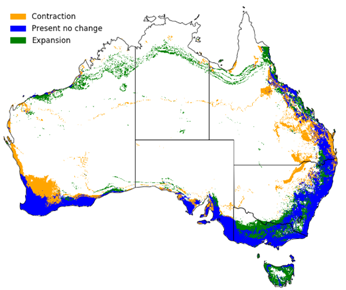

Climate Watch has modelled future habitat suitability of the Christmas Spider for the year 2070 under a climate change scenario. Figure 7 shows how the range of the species might change between now and 2070, with orange areas indicating where the species might disappear, green areas where the species range might expand, and blue areas where the habitat is predicted to be suitable for the species now and in the future. Please note that while these models can be very informative, they are only an estimated representation of the real world and thus should always be viewed with caution (ClimateWatch 2019).

Integrate Sustainability has extensive experience in managing baseline studies and Environmental Impact Assessments; if you or your business needs assistance undertaking baseline surveys or monitoring please do not hesitate to give us a call 08 08668 0338 or email enquiries@integratesustainability.com.au

Bibliography

Atkinson, Ron. 2011. “Austracantha minax.” Friends of Queens Park Bushland.

ClimateWatch. 2019. ClimateWatch. Accessed 12 10, 2019. https://www.climatewatch.org.au/species/spiders/christmas-or-jewel-spider.

Framenau, Volker W. 2014. “”Checklist of Australian Spiders Version 1.29″ (PDF).” Australasian Arachnological Society Retrieved 3.

Sinclair-Jones, Michael. 2013. “”Christmas Spider” .” Edited by 4 Toodyay Naturalists’ Club Inc. pp. 3&ndash. In Desraé Clark – The TNC Newsletter 12.

The Atlas of Living Australia. 2019. The Atlas of Living Australia – Occurrence records map (271 records). Accessed 09 12, 2019. https://bie.ala.org.au/species/urn:lsid:biodiversity.org.au:afd.taxon:36b436b1-3dc2-487d-8386-8bf3f3972e40.

Waldock, J. M. and Scharff, N. 2014. “Notes on the generic name of the Christmas or Jewel Spider, Austracantha minax (Thorell).” Australasian Arachnology 59: 4-5.