Download PDF: ISPL Insight – Tragedy of the Commons and Environmental Management

What is the “Tragedy of the commons”?

“The Tragedy of the Commons” is a term used to describe what happens to community resources as a result of human greed. It was first coined in an article in Science in 1968 by Garrett Hardin. At its core, the Tragedy of the Commons demonstrates that, when something is owned by a group (not privately owned), the overall sustainability can be impacted because no single person technically owns it or is responsible for it. The tragedy lies in the fact that when no one person owns the resource, everybody is open to taking from it, even if it is beyond their fair share or is not sustainable. The commons dilemma was seen long before Hardin, but he brought widespread attention to it and described it in a layman term making it easier to understand.

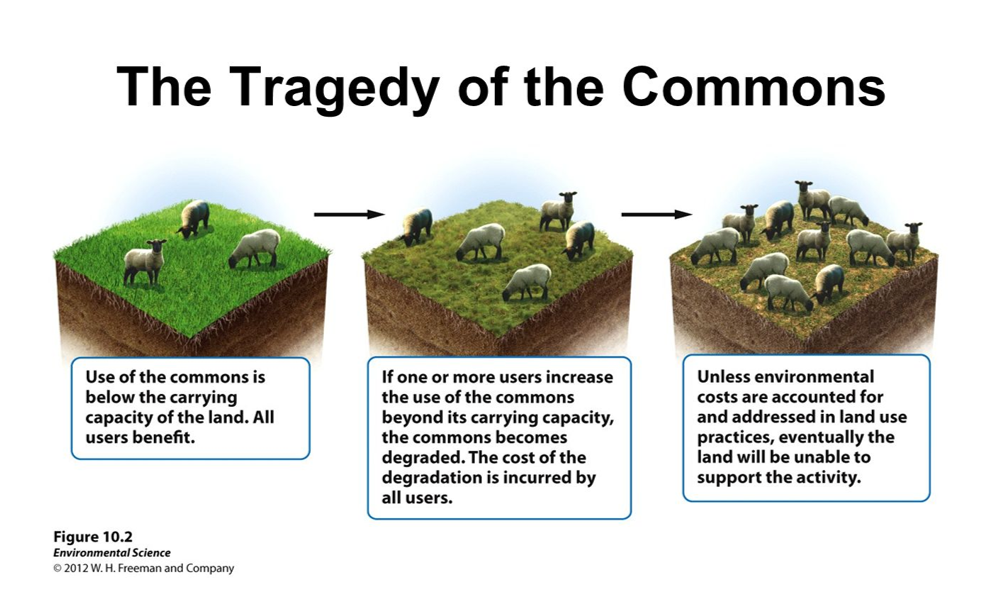

The example Hardin uses to illustrate the Tragedy of the Commons is of a group of farmers and a shared land area. Each farmer is assumed to be keeping their own cattle on the land, from which they yield a personal profit, but the land is assumed to be collectively shared, or leased from a government. Each additional head of cattle has a cost and a gain associated with it. The cost is in land use and wear on the land, while the gain has to do with the profit that can be reaped from that cattle. The trick is, when a farmer adds a cow to his herd, he gains all the benefit of the extra cow, while sharing only a small portion of the cost in terms of land use.

It is therefore rational, in a strict short-sighted view, for a farmer to try to increase his herd as much as he can. And in fact, that view could work out quite well if only one farmer were to take it. But, since it is a rational course of action, we can assume all of the farmers will pursue it, at which point the land will become degraded preventing it use, and all parties lose. This is the Tragedy of the Commons, the loss of common space through individual pursuit of a rational course of action. Since actions are not taken in a vacuum, what seems like a smart strategy is in fact wrong.

The Tragedy of the commons can be applied to any sort of common resources. The question that arises is how do we manage resources that seem to belong to everyone? Natural food reserves such as fisheries, energy resources like fossil fuels, a clean environment, with clean air, water (e.g. rivers and groundwater) and soil are examples of resources that belong to everyone and yet are protected by no one. When resources are commonly owned who has the responsibility to make a call to action? Today, protecting such common-pool resources has become a challenge, not only on the local scale but on a national and global scale as well.

The Tragedy of the commons can be applied to any sort of common resources. The question that arises is how do we manage resources that seem to belong to everyone? Natural food reserves such as fisheries, energy resources like fossil fuels, a clean environment, with clean air, water (e.g. rivers and groundwater) and soil are examples of resources that belong to everyone and yet are protected by no one. When resources are commonly owned who has the responsibility to make a call to action? Today, protecting such common-pool resources has become a challenge, not only on the local scale but on a national and global scale as well.

The Tragedy of the Commons can be likened to the now popular term ‘Sustainable Development’, as both refer to the need to appropriately and cooperatively manage shared resources, in order to maintain a balance between different generations of people inhabiting a particular niche within an urban or rural ecosystem. The definition of sustainable development provided by the Brundtland Report is “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. As such, sustainable development can be viewed as one of the main solutions to the Tragedy of the commons.

Solution to Governing the Commons: The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

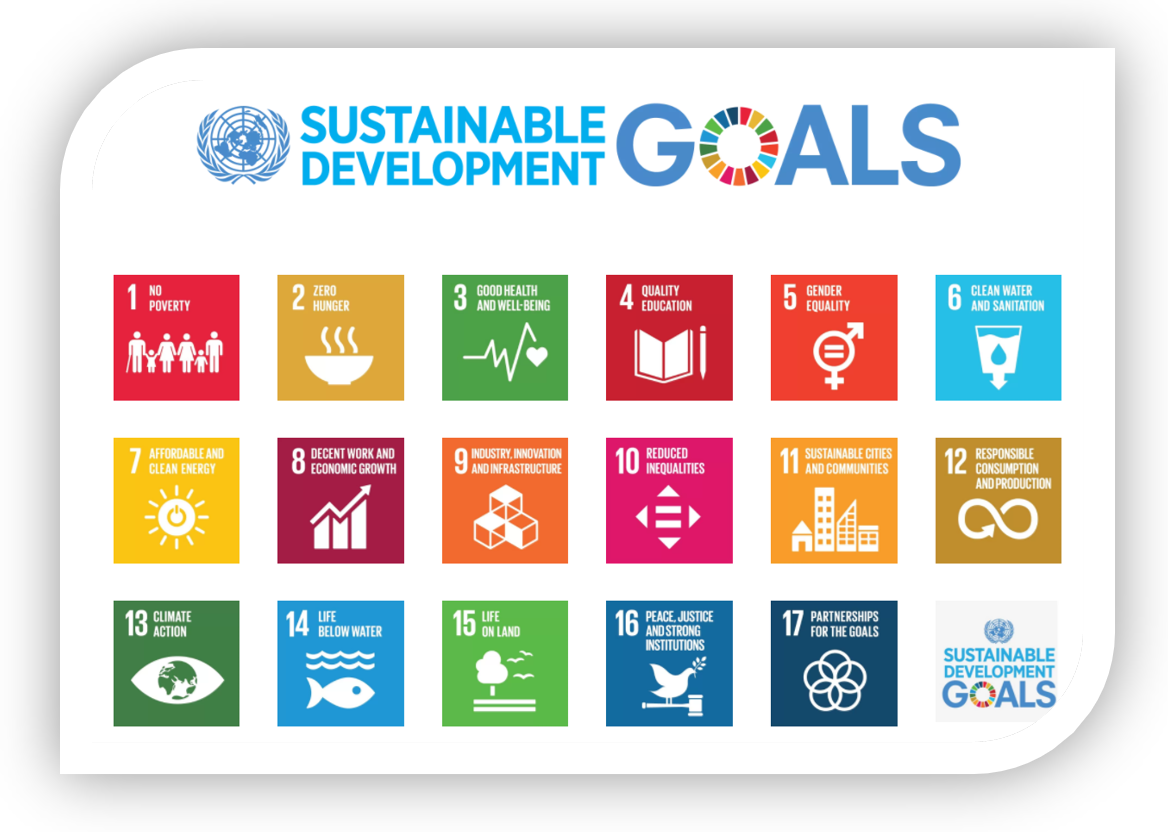

Officially known as Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the SDG agenda is an action plan framed around people, planet and prosperity through to 2030, seeking a better, sustainable world for all.

The 2030 agenda set 17 goals and 169 targets, that can be thought of as a form of DNA, of sustainable development from planning to implementation to people and the protection of the environmental. Each of the 17 goal has specific targets to be achieved by 2030 and they can be found at http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/, and are listed below:

- No poverty

- Zero hunger

- Good health and well-being

- Quality education

- Gender Equality

- Clean water and Sanitation

- Affordable and Clean Energy

- Decent Work and Economic Growth

- Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure

- Reduce Inequalities

- Sustainable Cities and Communities

- Responsible Consumption and Production

- Climate Action

- Life below water

- Life on land

- Peace, Justice and strong institutions

- Partnerships for the goals

These goals and targets are universal, and reaching the goals requires action on all fronts – governments, businesses, civil society and people everywhere all have a role to play. For the goals to be reached, everyone needs to do their part: governments, the private sector, civil society and people like you.

The SDGs represent goals and targets that can make Australia more prosperous, fair and sustainable and also encourage actions by Australia that will contribute to global sustainable development, for example a more sustainable consumption and production, reduced carbon emissions, and support for overseas development.

Solutions at a community level

Elinor Ostrom (an expert in public policies that was awarded the Nobel in Economics in 2009) offered 8 principles for how commons can be governed sustainably and equitably in a community and found many examples from local communities – small traditional groups with high social capital, that have often created collective solutions to the tragedy of the commons by themselves. The 8 Principles for managing Commons include:

- Define clear group boundaries.

- Match rules governing the use of common goods to local needs and conditions.

- Ensure that those affected by the rules can participate in modifying the rules.

- Make sure the rule-making rights of community members are respected by outside authorities.

- Develop a system, carried out by community members, for monitoring members’ behaviour.

- Use graduated sanctions for rule violators.

- Provide accessible, low-cost means for dispute resolution.

- Build responsibility for governing the common resource in nested tiers from the lowest level up to the entire interconnected system.

Ostrom has documented in many places around the world how communities devise ways to govern the commons to assure its survival for their needs and future generations. A classic example of this was her field research in a Swiss village where farmers tend private plots for crops but share a communal meadow to graze their cows. While this would appear a perfect model to prove the tragedy-of-the-commons theory, Ostrom discovered that in reality there were no problems with overgrazing. That is because of a common agreement among villagers that no one is allowed to graze more cows on the meadow than they can care for over the winter—a rule that dates back to 1517. Ostrom has documented similar effective examples of “governing the commons” in her research in Kenya, Guatemala, Nepal, Turkey, and Los Angeles.

Ostrom has documented in many places around the world how communities devise ways to govern the commons to assure its survival for their needs and future generations. A classic example of this was her field research in a Swiss village where farmers tend private plots for crops but share a communal meadow to graze their cows. While this would appear a perfect model to prove the tragedy-of-the-commons theory, Ostrom discovered that in reality there were no problems with overgrazing. That is because of a common agreement among villagers that no one is allowed to graze more cows on the meadow than they can care for over the winter—a rule that dates back to 1517. Ostrom has documented similar effective examples of “governing the commons” in her research in Kenya, Guatemala, Nepal, Turkey, and Los Angeles.

Have you participated in sustainably managed community projects or seeking assistance with planning your project? Are you or your organisation require assistance with planning for a sustainable business or need to help to manage your environmental risk please give Integrate Sustainability a call (08) 9468 0338 or email enquiries@integratesustainability.com.au.

If you are an individual and would like to take action to contribute to sustainable development http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/takeaction/ offers some ideas on what individuals can do to help.